This article acts as introduction to these exotic and incredibly ornamental tropical ferns, commonly known as Staghorn Ferns. Some suggestions on cultivation and the various species will be discussed.

There are nearly two dozen of species of Platycerium and more and more end up in cultivation every year. However, most are quite rare and many of those are also relatively fastidious. But a few are fairly easy and rewarding species to grow up from small plants on up to large behemoths.

These plants are tropical epiphytes. They grow on the sides of tree trunks, rocks and walls in nature. All ferns start out is microscopic spores. In the humid tropics, where it never gets cold or rarely dry, the spores have the perfect environment to grow in. Though it still amazes me how a huge, 100-pound fern can have started out as single spore, somehow attach to a wall, and then grow on a sheer vertical structure many feet off the ground and not fall down. Since most of us don't live in the tropics, the following are some suggestions to grow a Staghorn Fern in your less-than-tropical garden.

Platycerium bifurcatum growing on a palm in cultivation

Platycerium bifurcatum growing on a palm in cultivation

Platyceriums basically consist of 3 parts: the roots (small and sometimes hard to see), sterile or basal fronds (which eventually dry up and form the ‘shield' or rounded base of the Staghorn fern) and the foliar fronds for which these beautiful ferns are named after (look a bit like a deer's antlers). It is on these latter fronds that the spores form, which are the reproductive structures of the ferns.

Shield fronds Shield of dried fronds with foliar fronds growing from 'eyes' foliar fronds showing spore (all photos ginger749)

Most small ferns are sold in pots, though sometimes one can purchase one already mounted on a board. Though many will grow in pot for a while, most quickly outgrow pots. Additionally it is way too easy to overwater one in a pot full of soil and most Staghorn ferns rot easily if overwatered.

young plants being sold in pots at nursery- older plants in larger pots on right

However, this is usually how Staghorn Ferns are sold- on boards (photo on left shows larger variety being offered at a plant show)

Ferns can be grown much longer in wire baskets with potting soil, usually kept in by layers of sphagnum moss, coir or some porous synthetic material. Ferns grown in baskets will usually pup and grow so that eventually ferns will be growing out in a 360-degree pattern (or 180 degrees for flat-sided baskets that mount on walls). Eventually many ferns will even outgrow all but the largest metal baskets, and may require cable to support them.

Platycerium bifurcatums growing out of a basket initially (left) and a year later (middle); huge specimen growing in a sphere suspended by a chain (right)

Most grow their ferns on vertical surfaces, however, as that is how they grow in nature. A hanging fern makes a great ornamental adornment for any large tree or wall in the garden. For a substrate, most simply use a flat board (something that will take years of water without deteriorating too rapidly... plywood is not a good choice as it tends to peel apart quickly). Mounting a fern is not too difficult and there are dozens of ways people come up to do it. The basic plan is to place the fern on the surface with the small roots and basal fronds (the shorter, rounder ones that make up the solid base of the fern) sitting on top a mound of growing material. This growing material can be potting soil, sphagnum moss, peat, compost etc. Then one needs to affix the fern securely to this board either with wire (for some reason, copper wire is NOT recommended), nylon (high test!), plastic strips or mesh, or even nylon hose. If the fern is flattish it can sometimes even be nailed to the board with short roofing nails with large, wide heads. Large, thick ferns cannot be mounted with nails, however. I have also used chain, bungee cords and plastic-coated cable for larger ferns. This is also because I have squirrels which eat through most anything smaller and I kept finding ferns lying on the ground. Be sure to strap, tie or nail the fern over/through the dead, brown shield fronds, not over the soft, green fronds or they will be badly damaged or die. Here is a link to one method of mounting a small fern to a specially made board: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=syY09Wrvp7s

Above is my Platycerium andinum as I acquired it, and after I wired to a board I created (...so, I'm not a professional, OK?)

If one eventually wants to grow their fern on a tree trunk it helps to initially grow the fern on a curved substrate. For this one can use dried tree fern trunks, or another method I have seen that worked well was to grow the ferns on specially prepared PVC pipe. To grow ferns on PVC, one first wraps a large section of PVC in one to two inches of sphagnum moss and then tightly wraps the moss with chicken wire or hardware cloth (wire mesh). Then one simply ties the small fern to this structure with nylon or wire. The ties can eventually be removed as the fern grows into the moss/wire bedding. These PVC sections are conveniently easy to hang and are fairly light compared to a large wooden board.

Not a great photo, but these are sections of PVC with Staghorns growing on a mesh over moss. As these age, they will wrap around the PVC pipe in a curve, 'ready-made' for affixing to tree trunks

Putting the fern on a tree can be challenging if the ferns are heavy. Sometimes I find a large tree with a fork in it and just drop the fern there, tying it temporarily into place. Most ferns eventually grow into the trees and the ties will no longer be necessary. Some recommend NOT to wrap ferns around tree trunks as this point of contact is a good place for fungal infections to start, eventually injuring or killing the tree or fern. However, I have not found that to be a common occurrence in my climate in southern California... perhaps in a humid climate is more likely to occur. Palm trees often make excellent trees for mounting ferns on, particularly those with fibrous matting on them.

On the left is a large fern I strapped to an Italian Cypress with stockings and rope- in 3 weeks the squirrels had eaten through all of that and it all fell down. Now it's hanging up with the aid of a chain, bungy cords and cable.. and holding so far; on right is a huge fern that would probably take a crane or some lever apparatus to hang as it weighs well over 150 pounds (someone else hung that one at botanical gardens)

Most ferns need little further care other than water, some nutrition and protection from the elements. Hanging ferns are not so easy to overwater as all the water drains off them immediately. However if watering one all day long one can still manage to rot a hanging fern. Most of the common species of Platycerium are fairly drought tolerant and handle being dried out to the point of wilting, but not for too much longer. The most common causes of Staghorn fern loss is over and under-watering (the latter is particularly easy to do in my summer climate, where it gets over 100F frequently and there is little humidity). For this area, daily watering , or at least misting, is recommended in hot, dry weather. The larger the plant, the more tolerant of over and under-watering they seem to become. I have seen many fern growers simply toss a smaller, mounted dehydrated fern into a pond or a large pot of water for a few hours, then re-hang them.

Some recommend little to no fertilization of Staghorn ferns, but most recommend at least some liquid fertilization monthly during the warmer seasons with a balanced solution (1:1:1). A slow-release fertilizer can be used if placed on the organic substrate of larger ferns in small amounts. Some recommend other organic material be placed there as well. For some reason (the potassium, perhaps?) banana peels are frequently recommend. I have used these periodically and they seem to at least be tolerated well... but in area, the squirrels quickly abscond with these. Also, bananas attract other pests as well, and may end up doing more harm than good. Organic material that falls from trees is also frequently used by the tree ferns (some feel pine trees do NOT make good choices to tie ferns onto since their organic droppings are somewhat toxic to fern roots).

Most species of Platycerium do not tolerate much cold. Though some websites say ferns do not like temps below 55F, I have not found any of the common species to mind temperatures down to about 32F, and a few take moderate frost fairly well (down to about 27F). Below that, most show at least some leaf damage, though many will survive temperatures a few degrees lower and re-grow eventually.

These are two of the most cold tolerant species, Platycerium bifurcatum and Platycerium veitchii... however a half-day freeze down to 25F in my yard killed the bifurcatum and defoliated the veitchii

Arid heat is more of a limiting factor in my climate. Most Staghorn ferns do not like it hot and dry. My beautiful Platycerium superbum tolerated our severe freeze several years ago fairly well but the blistering heat of the following summer really did it in. You can battle this problem by setting up automatic misters as most of these plants will tolerate high heat as long as they are somewhat moist.

Most Staghorn ferns like bright light, but some protection from hot sun. A few species here in the hot desert of inland southern California actually tolerate some full sun, but most do not. That is one of the reasons these do well on tree trunks, as the tree branches offer midday sun protection.

Fern growing on a palm gets very little mid-day sun; these ferns in middle photo get morning sun only in California and are doing fine; photo on right shows large ferns on two King Palms that have been topped and are now exposed to full sun, and are doing OK in California... but most Staghorn ferns could not handle this exposure in out climate.

Propagation is by either growing them from spores (something I have never managed to do) or from division (taking off small pups). For more on growing fern from spores, see these tips offered on the Brooklyn Botanic Garden website. To divide a fern, one must first identify a sucker or pup, and carefully cut it off with a sharp knife or scissors, taking at least some of the roots. These suckers can be found by looking under the dried, brown shield fronds and looking for the little rhizomes coming off the larger plant. It is best to cut into the fern when the latest shield frond is brown, no green or fuzziness left in it. The center of each rosette of leaves is often called the ‘eye'. Large ferns have many eyes, and all these can potentially be divided into individual ferns, but the fewer pieces one cuts the fern into, the more likely each section will survive. Then begin the sucker as one would initially mount a fern as described above.

Problems usually involve something amiss with the watering or humidity and those have already been discussed. Staghorns ferns are also damaged by pests, easily. Snails can ravage these plants, but the primary dangers (in cultivation) are birds and squirrels.

Platycerium superbum with snail damage; Platycerium veitchii with bird damage (parrot mostly)

Platycerium bifurcatum in its original condition on left; 1 year later after squirrels have been using for bedding and just shredding for 'fun'

By far the most commonly grown Staghorn fern is Platycerium bifurcatum (aka common staghorn fern or elkhorn fern). One of the reasons this species is so common is it is so easy to grow (and reproduce). And for this reason it is relatively inexpensive. This is probably the best species to start with for novices. This is a fern native to the moist, coastal regions of eastern Australia, and in New Guinea. Old plants get fairly large (several hundred pounds) and develop hundreds of arching to dangling fronds of bifurcating fronds. These ferns do not develop the long, trailing fronds or the large upright fronds of some of the more impressive species, but they are indeed ornamental plants. This plant is tolerant of some sun (not hot, dry sun), cold (down to about 27F) and drought.

Platycerium bifurcatums in California

Platycerium bifurcatums in California

Platycerium veitchii is another very hardy species and about as easy to grow as Platycerium bifurcatum. It is less common perhaps because it does not get as large, nor does it grow as fast. But few species tolerate more full sun that this one. This is another Australian species, adapted to growing on open rock faces in semi-arid climates. The fronds of this species are blue-grey and fuzzy making it look quite different from most of the other Staghorn varieties. Not only does this one tolerate a lot of sun, but it is cold hardy down to about 25F without damage.

Platycerium veitchiis

Platycerium hillii is another Australian species from the wetter tropical areas. This plant is also somewhat smaller than Platycerium bifurcatum, but it is a gorgeous fern having bright green fronds, with wide bifurcations of both the foliar and shied fronds. This one is much harder for me to keep alive in summers as it really does not tolerate drought and heat well (together). It also has very little tolerance for hot sun, though older plants can take some in the mornings.

Platycerium hilliis outdoors in California

Platycerium hilliis outdoors in California

Platycerium hilliis on boards in protected locations

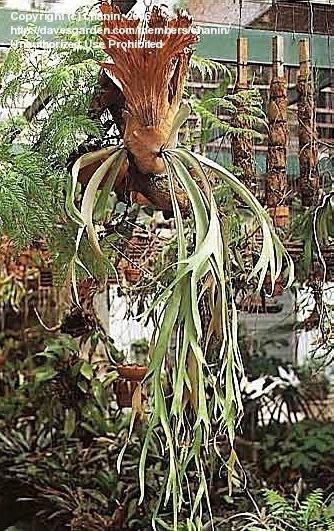

Probably the second most commonly grown Staghorn in cultivation is Platycerium supberbum, a massive species from eastern Australia. Despite its being a commonly grown fern, it is not one of the easiest to grow, being a bit touchy about cold, heat and overwatering. Additionally this is not a pup-forming species so these plants can only be grown from spore (hence they tend to be fairly expensive). Still, most fern growers consider it to be an ‘easy' species. This east Australian native is known for its huge ‘nest' fronds (modified shield fronds) which are upright, wide, bifurcating fronds that form a nest for trapping leaves and other organic material which it feeds itself with. These nest fronds also are how this fern wraps itself around trees, covering the small rhizomes and roots beneath that grow into the wood. It also develops long, ornamental foliar fronds that dangle two to three feet below the body of the fern making this one of the most dramatic of all the Platycerium.

Platycerium superbums in California

Platycerium superbum in California; my own younger plant (before heat killed it); shot of plant on palm from below- dark areas are spores on lower fronds

The only species I have grown is Platycerium andinum, which is the only Staghorn from the New World (Peru). I find it a picky species in my climate, but it keeps growing year after year... just doesn't look good in the middle of the summer. It is another fairly large species and moderately tolerant of hot sun (as long as remember to water it frequently). It eventually forms tall nest fronds and a few trailing foliar fronds. If grown on a tree it eventually will form a ring completely around it, but it is very slow to do this.

my own young plant (left)

my own young plant (left)  Southern California ferns

Southern California ferns

There are about 12-15 more Platycerium species but all are fairly uncommon and most are quite fastidious. The following is a link to a discussion of most of the species growing in cultivation with some comments on how difficult they are as well. Start with some of the above species and once you get to be an expert you can start seeking out the rarer and unusual species.

Platycerium coronarium in California; Platycerium coronarium in Hawaii; Platycerium elephantotis in Hawaii

Platycerium ellisii in California ; Platycerium holttumii in California Platycerium holttumii in Thailand (photo chanin)

Platycerium quadrichotomum (photo Chanin); Platycerium stemaria in California; Platycerium wallichii in Thailand (photo Chanin)

Platycerium wande in Thailand (photo Chanin); Platycerium willinckiis in California and in Thailand (second photo Chanin)

Copyright © www.100flowers.win Botanic Garden All Rights Reserved